Fernand Léger: When Machines Became Beautiful

People have started asking me to write about different artists. This week, my daughter suggested Fernand Léger. I'd seen his work in museums - those strange paintings where factory workers look like robots and city scenes feel like blueprints. Most artists of his time viewed machines as a threat to art, but Léger saw something different. Learning Léger’s story changed how I think about his work.

A Farm Boy in Normandy

Joseph Fernand Henri Léger was born on February 4, 1881, in rural Argentan, Normandy. He grew up surrounded not by paintings but by the practical world of his father's cattle farm. His parents dreamed of him pursuing a sensible career, and at first, that's exactly what he did. He apprenticed with an architect in Caen, where he learned about precision and structure.

But Léger had bigger dreams. After completing his military service, he moved to Paris in 1900 with only a few francs in his pocket. Living in a tiny apartment and working as an architectural draftsman to survive, he was initially turned away from the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. But that didn't stop him. He attended classes anyway, studying at both the École and the Académie Julian, all while working to support himself.

The Man Who Painted Like an Engineer

Léger approached painting like an engineer approaches a blueprint. His figures weren't soft and organic but constructed from tubes, cones, and cylinders. This wasn't just a stylistic choice. It was his way of showing that humans and machines were becoming increasingly interconnected in the modern world.

His style was so distinctive that critics had to invent a new term for it: "Tubism." The name came from his habit of breaking down everything – people, objects, buildings – into cylindrical and tube-like forms. While other Cubist artists were using angular shapes and flat planes, Léger's world was all curves and volumes, like the parts of a well-oiled machine.

But it was World War I that truly changed him. From 1914 to 1917, Léger served on the front lines at Argonne and Verdun. Instead of being horrified by the mechanical nature of modern warfare, he found inspiration in the most unlikely places. His friend, Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg, wrote that Léger would draw during rest hours, in dugouts, and even in the trenches, often on wrapping paper that still bore the marks of rain and battle.

The experience transformed his art completely.

"My experiences at the front and the daily contact with machines led to the change which marked my painting." - Fernand Léger

The mechanical precision of military equipment and the industrial scale of warfare confirmed his belief that machinery was the defining feature of modern life.

The City That Changed Everything

In 1919, fresh from his wartime experiences, Léger painted what many consider his masterpiece: "The City." Looking at it feels like stepping into the chaos and energy of modern urban life.

The painting broke all the rules: no single focal point, no traditional perspective. Instead, you're immersed in a kaleidoscope of architectural fragments, advertisements, and human figures, which is exactly how we experience cities in real life.

Masterworks of the Machine Age

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Léger's creativity exploded across different mediums. His 1921 painting "Three Women" turned human figures into beautiful machines, using his signature tubular forms to create a new kind of portrait.

The "Builders" series celebrated the dignity of labor, comparing workers to the structures they created.

In "The Grand Parade" (1954), Léger combined all his themes – mechanical forms, bold colors, and everyday people – into a triumphant celebration of modern life.

But Léger wasn't content with just painting. He designed sets for avant-garde films and ballets, including the revolutionary Ballet Mécanique (1924).

The Artist of the People

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Léger believed art shouldn't be locked away in fancy galleries. A committed socialist, he created posters and murals for public spaces, determined to bring art into everyday life.

He was one of the first artists to embrace advertising and consumer culture in his work, using bold block colors and graphic lines. His paintings featured everything from bicycles to bottles of wine, everyday objects transformed by his unique vision.

A Vision for Our Time

During World War II, Léger found refuge in America, where his influence reached new heights. Teaching at Yale University, he inspired a generation of American artists. His vibrant use of color and geometric forms helped pave the way for Pop Art, and his influence can be seen in everything from mid-century advertising to modern graphic design.

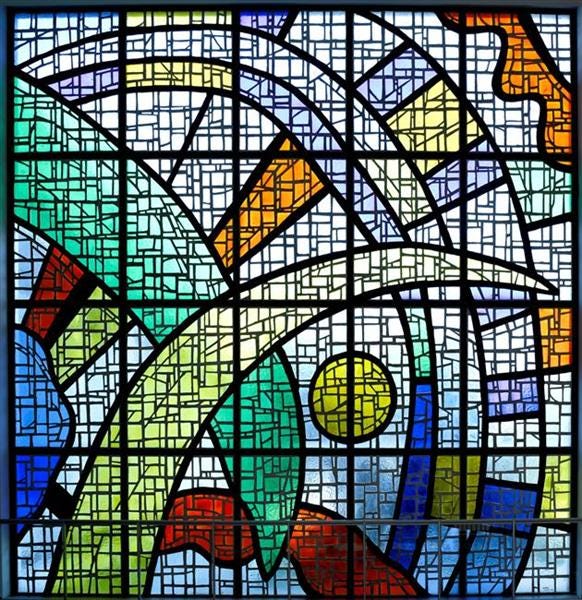

After returning to France, his creativity seemed to explode in new directions. In the final decade of his life, Léger created everything from stained-glass windows to ceramic sculptures. When he died at his home in Gif-sur-Yvette on August 17, 1955, he left behind more than just paintings. He left a new way of seeing the modern world.

Looking at Léger's work today, it's striking how he captured the pulse of the modern world. His mechanical figures and geometric cityscapes don't feel cold or alienating. They burst with energy and life. The same industrial elements that others saw as threats to art became his tools for creation.

Thank you! You have opened my eyes in a new way.