House of the Future: Charles Schridde's Impossible World

Sometimes the most fascinating discoveries come from unexpected places.

I spend most of my time researching and writing about the future of work. This week, I was reading Building a Better World Without Jobs by work futurist Andy Spence. His article included Charles Schridde's illustration of House of The Future. I was immediately mesmerized and wanted to learn more about this remarkable artist.

From Comics to Corporate America

Charles Schridde was born in rural Illinois in 1926. His artistic journey began, like many children's at that time, with a love for drawing comics. But unlike most kids who eventually put down their pencils, Schridde turned his passion into a profession. After studying at the American Academy of Art in Chicago, he started his career as a commercial artist in the 1950s, creating illustrations for various advertising agencies.

Schridde’s art stood out because of his unique blend of architectural precision and imaginative flair. His early work in advertising, particularly his architectural renderings, caught the attention of major corporations. However, it was his ability to infuse these technical drawings with warmth and humanity that eventually led to his most famous work.

The Future Through a 1960s Lens

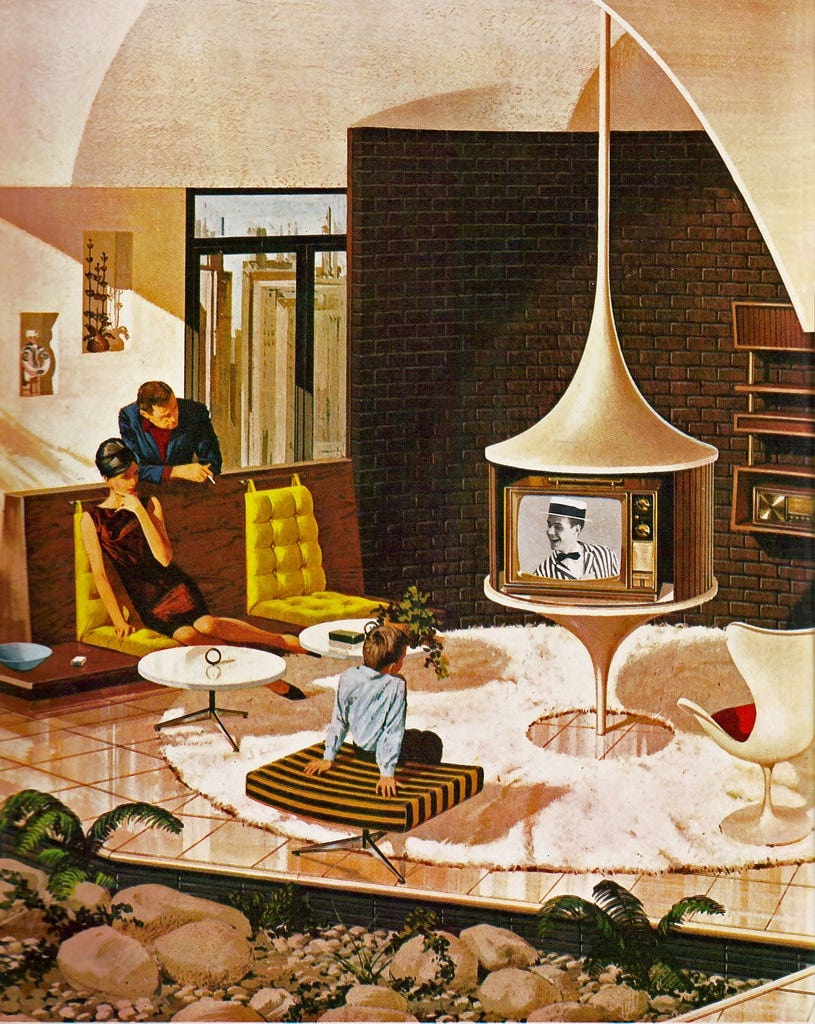

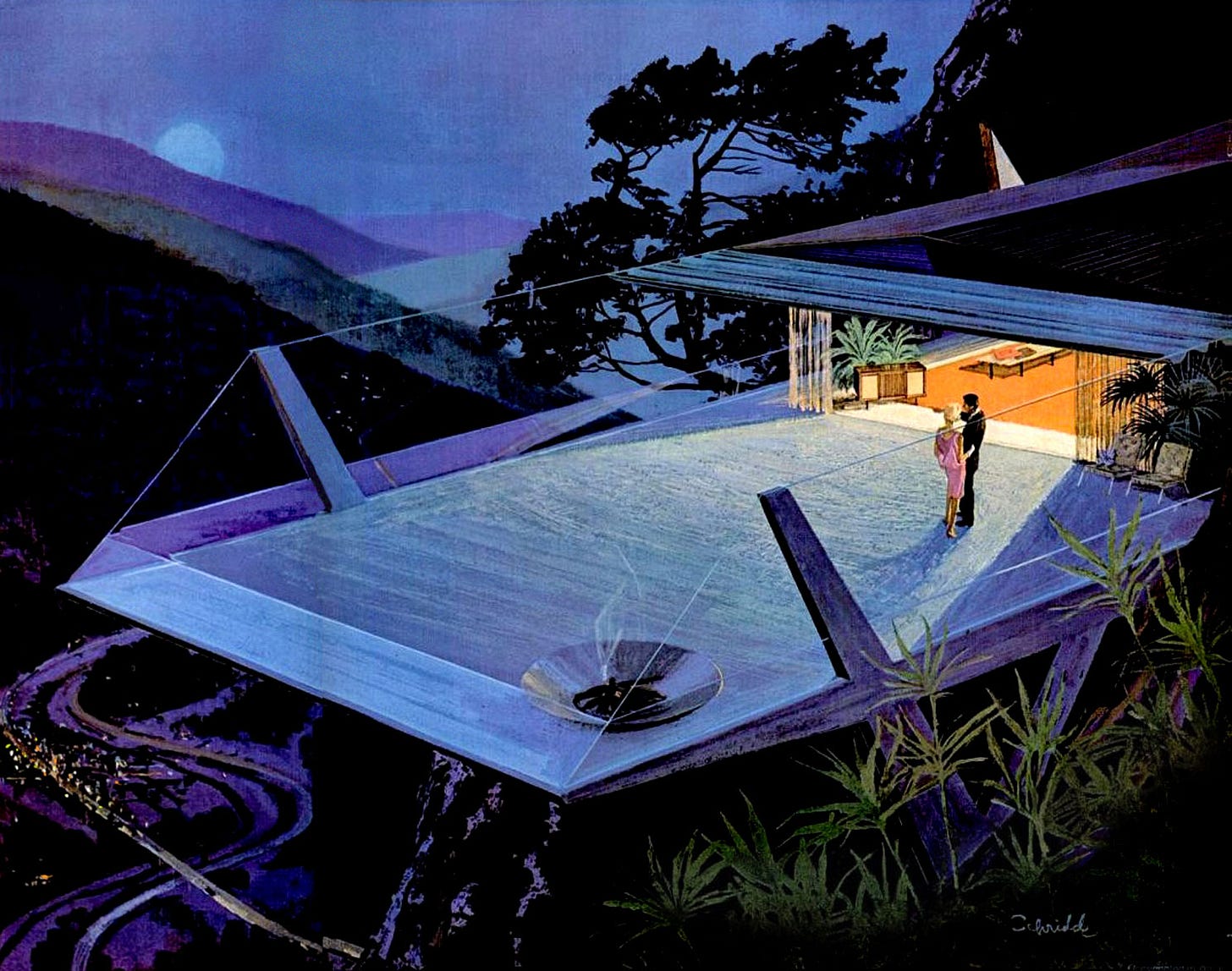

What made Schridde's vision of the future so compelling was how he made the extraordinary feel attainable. His homes weren't cold, sterile spaces filled with robots and flying cars. Instead, they were places where families lived, lounged, and loved, though in settings that defied gravity and convention.

These weren't just advertisements. They were windows into an optimistic future where modern technology enhanced rather than replaced human connection. In Schridde's world, a family could watch television in a living room suspended over a cliff, or enjoy breakfast in a glass-enclosed space station high above Earth. Somehow, it all seemed perfectly natural.

Breaking Free from Convention

Schridde faced a huge challenge to make the future feel both aspirational and accessible. In the early 1960s, when many Americans were just getting used to having television sets in their homes, he needed to create images that would push boundaries without alienating viewers.

The conventional wisdom of the time was to show products in realistic, relatable settings. But Schridde took a different approach. He believed that people didn't just want to see where they were. They wanted to dream about where they could be.

The Motorola Moment

In 1961, Motorola approached Schridde with an unusual request. They wanted him to create a series of advertisements that would position their televisions not just as appliances but as integral parts of the home of the future. This was his breakthrough moment.

The resulting "House of the Future" campaign became one of the most memorable advertising series of the 1960s. Each illustration showed a spectacular modernist home in an impossible location – perched on cliffs, suspended over oceans, or nestled in mountains – with a Motorola television as the heart of each space.

Masterpieces of Imagination

Schridde's most famous works for Motorola include homes built into cliffsides, with massive glass windows overlooking dramatic vistas. One particularly striking image shows a living room extending out over a canyon, with a couple relaxing while watching their Motorola TV, seemingly unconcerned by the steep drop below.

Yet another memorable piece features a home floating above the clouds, its geometric forms suggesting both stability and impossibility.

In each illustration, the integration of the television set feels natural and inevitable, despite the fantastic settings.

Redefining Advertising Art

The campaign's success transformed both Motorola's image and the advertising industry's approach to selling consumer electronics. These weren't just product advertisements. They were lifestyle statements that helped shape the public's perception of what modern living could be.

The illustrations appeared in major magazines across America, reaching millions of homes and inspiring countless conversations about the future of domestic life. They helped establish Motorola as a forward-thinking brand and elevated advertising illustration to an art form.

Today, Schridde's illustrations are celebrated not just as advertisements but as important artifacts of mid-century modernist optimism. His vision of the future – elegant, ambitious, yet fundamentally human – continues to inspire architects, designers, and artists.

His legacy can still be seen in contemporary art. For example, over the past year, I've been following the work of French artist Alexis Bruchon, whose pieces I first spotted at the Philippe Labaune Gallery. His work caught my attention precisely because it echoes Schridde's brilliant combination of architectural precision and imaginative possibility.