Jean Dubuffet and the Art of the Outsider

Something unexpected happened during my recent visit to the MUDEC Museum in Milan. Looking at Jean Dubuffet's raw, unpolished artworks, I felt a strange sense of freedom.

Here was art that broke every rule about what makes art "good," but it didn’t matter. A quote on the wall captured this feeling perfectly:

"True art always appears where you do not expect it. Where nobody thinks of it or utters its name. Art hates to be recognised and greeted by its name. It runs away immediately..." - Jean Dubuffet

These weren't just words on a wall. They were the core belief of Dubuffet, who spent his life challenging everything we think we know about art. Another quote in the exhibition revealed his unique way of seeing:

"You should look at things several times. And by changing the angle every time, never the same angle twice. Look at them once from above, once from below, once sidelong - especially sidelong." - Jean Dubuffet

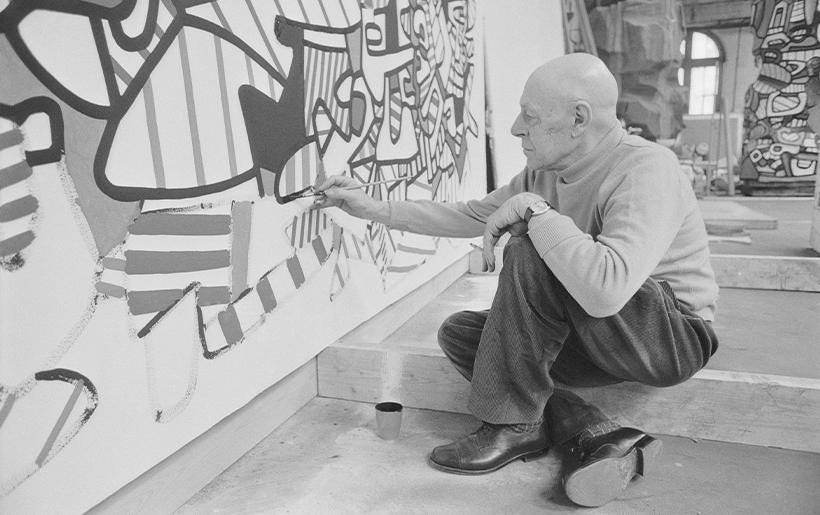

What if everything we knew about "good art" was wrong? This question drove Dubuffet, a successful French wine merchant who, at the age of 41, walked away from his comfortable life to become one of the 20th century's most controversial artists.

From Wine to Wild Art

Born to a wealthy family of wine merchants in Le Havre, France, in 1901, Jean Dubuffet seemed destined for a conventional life in the family business. He briefly studied art in Paris but dropped out after six months, declaring traditional education "stifling." For two decades, he dutifully sold wine, making a comfortable living while privately experimenting with art on the side.

The turning point came in 1942, during the dark days of World War II. At an age when most people settle into their careers, Dubuffet made the shocking decision to devote himself entirely to art. His wealthy friends thought he had lost his mind. But Dubuffet had discovered something that would become his life's obsession: the raw, unfiltered creativity of those who existed on society's margins.

Breaking Free from Convention's Chains

Dubuffet became fascinated by what he called "Art Brut" (Raw Art) - works created by people with no formal training, particularly those in psychiatric hospitals. He would spend hours in mental institutions, prisons, and on the streets, collecting thousands of drawings and sculptures made by people who had never set foot in an art school.

"It is not forbidden to imagine the interpretation of a word deciphered differently, regulated differently, than those which we have held until now in full confidence." - Jean Dubuffet

What struck him wasn't just the technical aspects of these works but their unfiltered emotional power. While trained artists worried about proper technique and pleasing critics, these outsider artists created purely for themselves, uninhibited by rules or expectations. This, Dubuffet believed, was what made their work so authentic and powerful.

Fighting the Art Establishment

The art world was horrified by Dubuffet's embrace of outsider art. Critics called his ideas dangerous and his own art "childish." Museums refused to show the Art Brut collections he had carefully assembled. Some even suggested that promoting the art of psychiatric patients was itself a sign of mental instability.

The establishment couldn't comprehend art that, as described in the MUDEC exhibition, "overlooked conventional and conformist codes, overturned the notion of the beautiful idea, and challenged the need for verisimilitude."

But that was exactly what drew Dubuffet to these works. They were, as the museum notes, "disconcerting and intriguing," forcing viewers to question their assumptions about art and beauty. They undermined traditional judgments and eliminated familiar points of reference.

The attacks on Dubuffet became personal. Fellow artists accused him of promoting "primitive" art just to shock people. Others claimed he was merely exploiting mental patients for his own fame. The criticism was relentless, but Dubuffet remained unmoved. He believed that true artistic expression couldn't be bound by rules or expectations.

The Breakthrough

In 1947, Dubuffet organized the first exhibition of Art Brut in Paris. The show created an uproar, but it also attracted supporters who recognized the authenticity in these unconventional works. Gradually, his ideas began to influence a new generation of artists who were tired of traditional rules and seeking more authentic forms of expression.

By the 1960s, Dubuffet's own art - inspired by the principles of Art Brut - gained international recognition. His childlike style, use of unusual materials (including butterfly wings and sponges), and rejection of traditional beauty standards helped pave the way for new forms of modern art.

Beyond Convention

Dubuffet's most significant works weren't just his paintings or sculptures, but the massive collection of Art Brut he assembled over decades. Today, the Collection de l'Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, houses over 70,000 works by hundreds of self-taught artists he discovered and championed.

His own artistic output was equally impressive. His "Hourloupe" series (1962-1974) became his most recognizable work - a collection of sinuous, puzzle-like patterns in red, white, and blue that seemed to pulse with energy.

The most famous of these is "Group of Four Trees" (1972), a towering 42-foot-high sculpture in black and white that still stands in New York's Chase Manhattan Plaza.

His "Texturologies" series of the 1950s looked like aerial views of the earth, created by sprinkling paint with a brush to form dense, speckled patterns.

A Legacy of Inclusion

Dubuffet's vision has transformed how we think about art today. Outsider Art fairs attract thousands of visitors worldwide, and works by self-taught artists command high prices at auctions. But more importantly, his ideas have helped break down the barriers between "high" and "low" art.

Dubuffet continued creating art until shortly before his death in Paris on May 12, 1985, at the age of 83. In his final years, he focused on creating massive public sculptures, bringing his unique vision to city spaces around the world. Even as his health declined, he remained committed to his belief that true creativity knows no boundaries.