Painting Happiness Through Depression with Norman Rockwell

When Norman Rockwell checked himself into a psychiatric facility in the 1950s, millions of Americans had his cheerful paintings hanging on their walls. How did a man battling severe depression create the most beloved images of American happiness?

This isn't just another story about a troubled artist. The truth is, Rockwell's battle with depression didn't diminish his art. It deepened it, allowing him to see and capture moments of genuine human connection that others might have missed.

The Awkward Boy Who Would Paint America's Dreams

Norman Rockwell was born in New York City on February 3, 1894. As a child, he was tall, thin, and awkward. His family moved frequently during his childhood, making it hard for him to form lasting friendships. However, these early experiences of being an observer rather than a participant later shaped his unique ability to capture intimate moments of American life.

His talent emerged early and dramatically. By 16, he was already designing Christmas cards professionally. At 18, he illustrated his first children's book, and by 19, he had landed the position of Creative Director at Boys' Life magazine.

Hundreds of Photos for One Perfect Moment

In his studio, Rockwell worked like a movie director orchestrating a scene. For each painting, he would stage elaborate photo shoots, taking hundreds of pictures from multiple angles. A child's crooked smile, a grandmother's weathered hands, a father's proud posture – each element had to be perfect.

Then, he would combine the best elements from different photos to create his perfect composition.

But this pursuit of perfection came at a cost. He would spend weeks on a single image, often working until exhaustion, skipping meals and sleep. Even then, he wasn't satisfied until critics had reviewed his work-in-progress, ensuring his visual storytelling was clear enough.

The Darkness Behind the Light

Despite his growing success, Rockwell faced severe bouts of depression and anxiety throughout his life. In the 1950s, he underwent treatment with psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, spending time in psychiatric facilities when his conditions became overwhelming. These struggles weren't widely known during his lifetime, making his ability to create such optimistic, heartwarming art all the more remarkable.

The contrast between his personal struggles and his public work reveals something profound about Rockwell. His art wasn't about depicting reality. It was showing people the world as it could be, offering hope and connection in times of uncertainty.

"I unconsciously decided that, even if it wasn't an ideal world, it should be. So I painted only the ideal aspects of it," Rockwell once said.

But as America changed, so did Rockwell's art.

From Apple Pie to Civil Rights

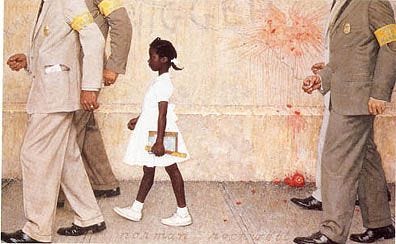

The turning point in Rockwell's career came in the 1960s. After decades of creating beloved but relatively safe illustrations for the Saturday Evening Post, he made a bold move to Look magazine. This shift allowed him to address serious social issues, resulting in works like The Problem We All Live With, showing a young Black girl being escorted to school by federal marshals during desegregation.

His most powerful work, The Four Freedoms series, inspired by President Roosevelt's speech, helped rally the American spirit during World War II. These paintings toured the country, becoming yearly traditions for many families alongside his cherished Christmas illustrations for the Post.

Rockwell's ability to tell entire stories in single frames didn't go unnoticed by America's greatest storytellers.

From Main Street to Hollywood

Rockwell's influence extended far beyond traditional art circles. Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, two of America's greatest filmmakers, became avid collectors of his work, drawn to his masterful visual storytelling.

Spielberg proudly displays Rockwell's Triple Self-Portrait sketch, while Lucas owns the original Peach Crop.

The 1994 film Forrest Gump even paid homage to Rockwell, recreating his famous Girl with Black Eye painting with young Forrest.

Presidents, Movies, and Coca-Cola

Over six decades, Rockwell created more than 4,000 artworks, including 321 Saturday Evening Post covers. He painted portraits of five presidents (Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan) and created iconic advertisements for brands like Coca-Cola and Jell-O.

His impact on American culture was officially recognized in 1977 when President Gerald Ford awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor. A year later, when Rockwell passed away at 84, First Lady Rosalynn Carter attended his funeral, highlighting his significance to the nation.

“The secret to so many artists living so long is that every painting is a new adventure. So, you see, they're always looking ahead to something new and exciting. The secret is not to look back.” - Norman Rockwell

A $50 Million American Dream

Perhaps it was Rockwell's own struggles that allowed him to see the light in humanity so clearly. Through his art, he defined what it meant to be a devoted parent, a curious child, a hard worker, a kind neighbor, and a good citizen.

His legacy continues to grow. His studio in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, now the Norman Rockwell Museum, draws hundreds of thousands of visitors annually. In 2008, Massachusetts named him their official state artist.

The value of his work has soared far beyond what he could have imagined. His painting Saying Grace, which earned him $3,500 in 1951, sold for nearly $50 million in 2013.

But the true measure of Rockwell's impact isn't in dollars. For a man who spent his life battling inner darkness, his greatest achievement was showing America its own light. Rockwell shaped how the nation saw itself, defining what it meant to be American.

Discovering the behind the scenes of a great artist is really fascinating, I think. In general, it is intriguing to discover some of the processes that are behind some works or reflections.

Thanks to this issue I came into contact with Rockwell's, discovering above all the human aspects of his work, the cultural influence and the transversal of his impact. Thanks for sharing!

This issue gave me several food for thought on storytelling, the power of images and much more.